https://anthropology.fas.harvard.edu/people/james-watson-0

條友幾勁,d廣東話一定仲好過d新移民

人類學家: 盆菜咁下欄都可以流傳咁耐係有原因

出地人頭

213 回覆

570 Like

41 Dislike

就係吹奏緊共產囉

所有人無階級一齊踎o係度食垃圾係幾咁美好

所有人無階級一齊踎o係度食垃圾係幾咁美好

乜冇用公筷?

支那式食物真係莫講話難食兼垃圾,就連美感都係零,一堆垃圾撈埋一齊就話係盆菜,人哋和式料理或西餐好講究美學,擺到最靚俾人食,點會求其撈埋一堆上枱等你自己班友爭嚟食

不過英國其實係有美食 詳細可以睇寫1984嗰位作者 佢曾經為英國美食問題寫鴻文辯護

諗起黃店盤菜

其實日本點會無盆菜

鍋物料理根本就係盆菜

盆菜亦唔係咩特別發明

鍋物料理根本就係盆菜

盆菜亦唔係咩特別發明

如果盆菜有問題咁就一定要鬼有關嘅連登仔屋企衛生問題 事關我屋企家族就冇呢個問題 明明係用家問題 成日都可以變咗做物品問題

明明係用家問題 成日都可以變咗做物品問題

明明係用家問題 成日都可以變咗做物品問題

明明係用家問題 成日都可以變咗做物品問題

*歸咎

marketing 教材

垃圾都吹到唔食唔得

垃圾都吹到唔食唔得

The men in our group were in their 50s and 60s; all were hungry.

Prize pieces of pork fat and bean curd were fished out by my landlord and presented to me, on top of my rice bowl; he later explained that he wanted me to try the best items before they disappeared (which they did, rapidly). Within 20 minutes every scrap of food had been consumed; the men then proceeded to finish their bowls of rice and drink small cups of French brandy presented by the host – who did not say a word or perform any type of ritual (other than to pour the brandy). When we finished eating and drinking, everyone in our group abruptly got up, walked to the door of the ancestral hall, and disappeared into the alleyways of the village. They did not acknowledge the host (the father of the new-born child) nor did they thank him, or anyone else, for the meal. One other aspect of the banquet was striking: there were no women eating in the hall. All participants, including the cooks, were male.

I later learned that our group of eight men consisted of two multi-millionaire emigrants (from Holland and Canada) home for a brief visit, one taxi driver, one vegetable farmer, two retired emigrants (from England), my landlord (retired), and a 26 year old visiting anthropologist. There had been no attempt to separate people into distinguishable status groups: The rich ate with the poor, squatting on the floor because the chairs and tables were occupied by those fortunate enough to arrive early. This was – to my outsider’s eye – a conscious, purposely designed rite of extreme egalitarianism: All attendees were equal and the only thing that mattered in respect to seating arrangements was chronology: first come, first served. I concluded that the sik pun pattern of dining was a leveling device that emphasized the fact that all attendees were equal in the eyes of their ancestors – who happened to be present as ancestral tablets on the hall’s altar.

After further discussion with village friends, I later concluded that the banquet also constituted a form of social recognition and legitimization for the host, or (as in the case described above) for the host’s male heir. All male elders (fu lao), aged 60 and above were collectively invited to the banquets, not as individuals but as a social category. Public invitations were posted in the village square: “All fu lao are hereby invited to a full-month banquet in XX hall, on [date].” Nothing more was needed and every elder who was physically capable of attending did so. Attendees did not present red envelopes (containing money) to the host. Nor did they comment on the quality of the food; to do so would have been considered a breath of etiquette

睇完原文先出聲啦

Prize pieces of pork fat and bean curd were fished out by my landlord and presented to me, on top of my rice bowl; he later explained that he wanted me to try the best items before they disappeared (which they did, rapidly). Within 20 minutes every scrap of food had been consumed; the men then proceeded to finish their bowls of rice and drink small cups of French brandy presented by the host – who did not say a word or perform any type of ritual (other than to pour the brandy). When we finished eating and drinking, everyone in our group abruptly got up, walked to the door of the ancestral hall, and disappeared into the alleyways of the village. They did not acknowledge the host (the father of the new-born child) nor did they thank him, or anyone else, for the meal. One other aspect of the banquet was striking: there were no women eating in the hall. All participants, including the cooks, were male.

I later learned that our group of eight men consisted of two multi-millionaire emigrants (from Holland and Canada) home for a brief visit, one taxi driver, one vegetable farmer, two retired emigrants (from England), my landlord (retired), and a 26 year old visiting anthropologist. There had been no attempt to separate people into distinguishable status groups: The rich ate with the poor, squatting on the floor because the chairs and tables were occupied by those fortunate enough to arrive early. This was – to my outsider’s eye – a conscious, purposely designed rite of extreme egalitarianism: All attendees were equal and the only thing that mattered in respect to seating arrangements was chronology: first come, first served. I concluded that the sik pun pattern of dining was a leveling device that emphasized the fact that all attendees were equal in the eyes of their ancestors – who happened to be present as ancestral tablets on the hall’s altar.

After further discussion with village friends, I later concluded that the banquet also constituted a form of social recognition and legitimization for the host, or (as in the case described above) for the host’s male heir. All male elders (fu lao), aged 60 and above were collectively invited to the banquets, not as individuals but as a social category. Public invitations were posted in the village square: “All fu lao are hereby invited to a full-month banquet in XX hall, on [date].” Nothing more was needed and every elder who was physically capable of attending did so. Attendees did not present red envelopes (containing money) to the host. Nor did they comment on the quality of the food; to do so would have been considered a breath of etiquette

睇完原文先出聲啦

盆菜食垃圾

係蛋炒飯

人地係教授 你得你都可以做教授

第日連登仔建到國就會打倒所有中國文化

在下認同,感覺上講講下會成真

雖然我都唔知盆菜有咩好食,亦憎班鄉黑,但圍村文化幾時變咗中國文化?

垃圾食物不嬲多人like

車仔麵,沙牛麵,漢堡包

車仔麵,沙牛麵,漢堡包

純粹貪方便啫

日本 的「盆菜」

御節料理

御節料理

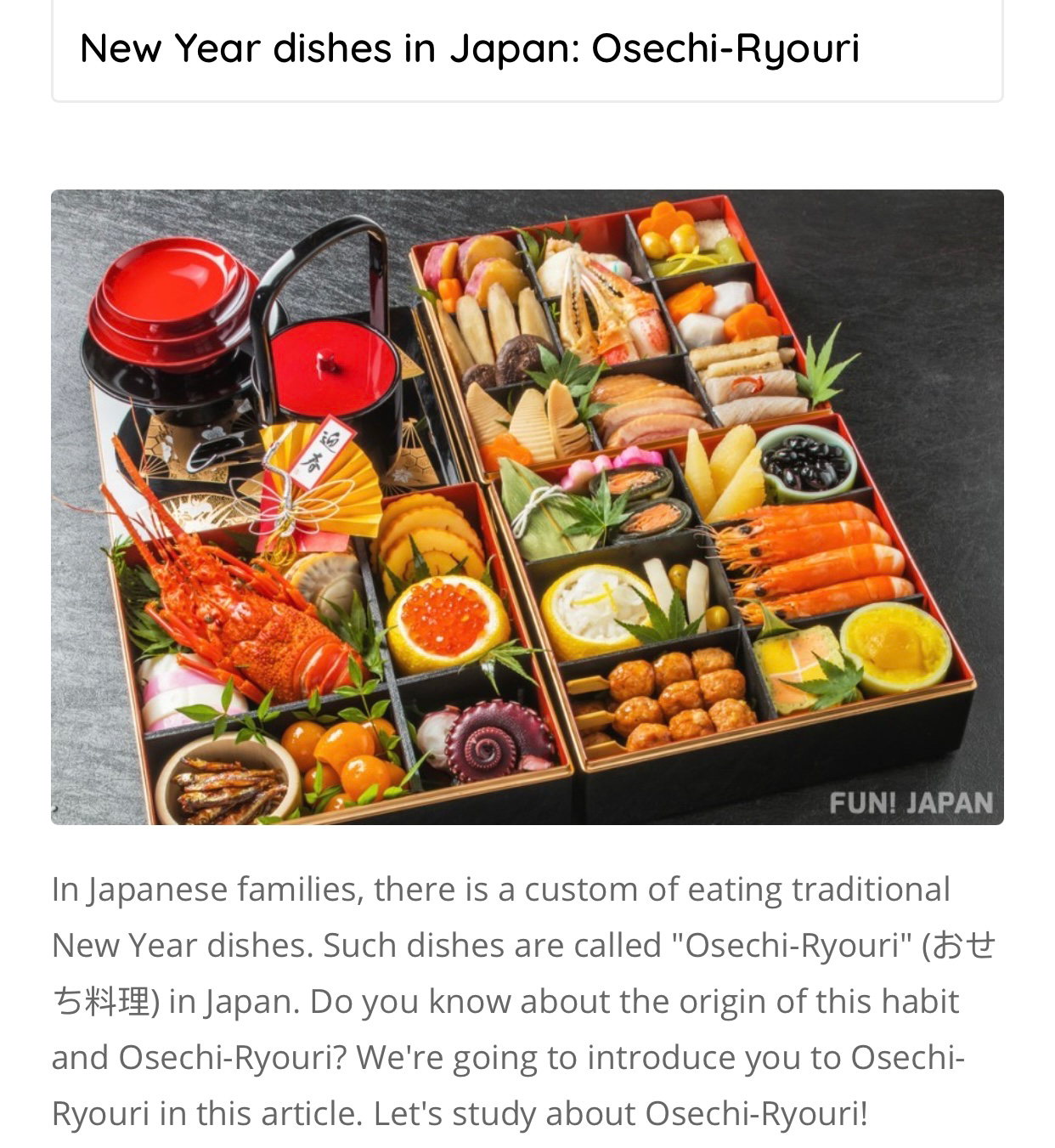

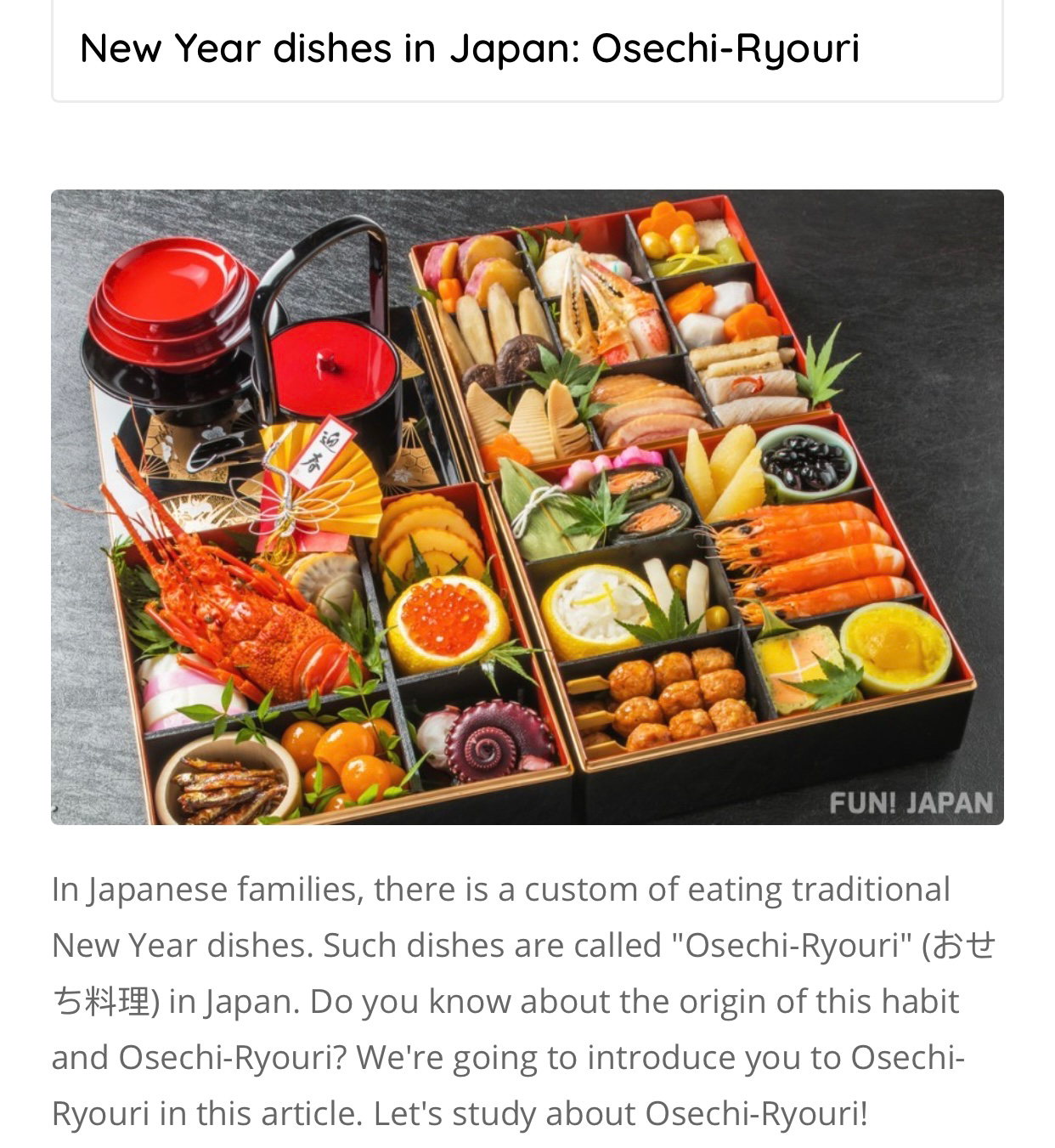

Osechi-Ryouri おせち料理

https://www.fun-japan.jp/en/articles/6650

https://www.instagram.com/p/CJpT9gng7VJ

御節料理

御節料理Osechi-Ryouri おせち料理

https://www.fun-japan.jp/en/articles/6650

https://www.instagram.com/p/CJpT9gng7VJ

+1

On99

平你老母等咩

你老細大大聲話要食魚蛋

唔通你班垃圾真係咁搶晒一粒都唔比咩

人類學家

狗也不屌

對人類知識幾乎冇貢獻

平你老母等咩

你老細大大聲話要食魚蛋

唔通你班垃圾真係咁搶晒一粒都唔比咩

人類學家

狗也不屌

對人類知識幾乎冇貢獻

而家D盆菜全部都唔係用下欄野啦,鮑魚螺片都有得你食