[香港保衛戰] 1941年11月16號: 加拿大軍抵達香港

雲加馬德里

61 回覆

73 Like

0 Dislike

推,呢排都睇緊空白的一百年

香港特區政府都介紹

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201112/22/P201112220347.htm

//一九四一年十一月十六日,兩營為數共約二千五百人的加拿大部隊-溫尼伯榴彈兵營和加拿大皇家來福槍營,乘坐巨型運輸艦抵港,加入香港守軍的行列。

溫尼伯榴彈兵營是一支加拿大步兵團,於一九零八年成立。第二次世界大戰初期,他們曾在牙買加駐兵十六個月。一九四一年十月,他們重回加拿大後不久便被派往香港服役。雖然兵團招收了一些新成員,但他們缺乏基本訓練,整體來說兵團是戰鬥力不足,而且還缺乏一個標準兵團應有的裝備。

加拿大皇家來福槍營成立於一八六二年,源於加拿大魁北克省魁北克市。槍隊在第一次世界大戰中積極參與戰事。第二次世界大戰期間,他們於加拿大東部的紐芬蘭省服役。一九四一年十月被召派前往香港。

兩隊加拿大援軍抵港不久,一切尚未適應,便得迎敵作戰。一九四一年十二月八日,日軍開始進攻港島,並極速地控制了港島東北柴灣至畢拉山的大部分地區,加拿大援軍立即部署反攻,力圖奪取畢拉山及渣甸山。可是,由於這兩支軍隊對地形不太熟悉,大大削弱戰鬥能力,緊守港島的援軍傷亡慘重,及至聖誕日下午三時二十五分,港督楊慕琦決定投降。

香港淪陷後,一千五百名加拿大戰俘被囚於北角戰俘營。與其他戰俘營一樣,北角戰俘營情況甚為惡劣,包括環境非常擠迫、糧食缺乏,以及醫療設備與其他設施嚴重不足。當時,有些士兵被送往日本當苦工,有些營養不良而患重病,當中部分人更因欠缺藥物治療而死亡。此外,戰俘被營內守衞拳打腳踢更是司空見慣。

直至一九四五年日軍宣布投降,這批加拿大士兵才得以重返家園。然而,當中卻有五百五十八名軍人魂斷異鄉,數目為一九四一年自溫哥華出發赴港兵員的五分之一以上。加拿大軍隊於香港保衞戰中奮勇抗敵,他們英勇的事蹟值得特別表揚。是次圖片展亦正好向於戰爭中犧牲的人致敬。

展覽透過一批珍貴的歷史圖片及文字展板,回顧加拿大軍隊參與保衞香港的英勇行為,當中更包括一頭隨軍團來港的加拿大犬─根達參與抗敵的感人故事。根達在鯉魚門(即現時海防博物館一帶)的戰役中奮力保護同袍,最後犧牲性命。//

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201112/22/P201112220347.htm

//一九四一年十一月十六日,兩營為數共約二千五百人的加拿大部隊-溫尼伯榴彈兵營和加拿大皇家來福槍營,乘坐巨型運輸艦抵港,加入香港守軍的行列。

溫尼伯榴彈兵營是一支加拿大步兵團,於一九零八年成立。第二次世界大戰初期,他們曾在牙買加駐兵十六個月。一九四一年十月,他們重回加拿大後不久便被派往香港服役。雖然兵團招收了一些新成員,但他們缺乏基本訓練,整體來說兵團是戰鬥力不足,而且還缺乏一個標準兵團應有的裝備。

加拿大皇家來福槍營成立於一八六二年,源於加拿大魁北克省魁北克市。槍隊在第一次世界大戰中積極參與戰事。第二次世界大戰期間,他們於加拿大東部的紐芬蘭省服役。一九四一年十月被召派前往香港。

兩隊加拿大援軍抵港不久,一切尚未適應,便得迎敵作戰。一九四一年十二月八日,日軍開始進攻港島,並極速地控制了港島東北柴灣至畢拉山的大部分地區,加拿大援軍立即部署反攻,力圖奪取畢拉山及渣甸山。可是,由於這兩支軍隊對地形不太熟悉,大大削弱戰鬥能力,緊守港島的援軍傷亡慘重,及至聖誕日下午三時二十五分,港督楊慕琦決定投降。

香港淪陷後,一千五百名加拿大戰俘被囚於北角戰俘營。與其他戰俘營一樣,北角戰俘營情況甚為惡劣,包括環境非常擠迫、糧食缺乏,以及醫療設備與其他設施嚴重不足。當時,有些士兵被送往日本當苦工,有些營養不良而患重病,當中部分人更因欠缺藥物治療而死亡。此外,戰俘被營內守衞拳打腳踢更是司空見慣。

直至一九四五年日軍宣布投降,這批加拿大士兵才得以重返家園。然而,當中卻有五百五十八名軍人魂斷異鄉,數目為一九四一年自溫哥華出發赴港兵員的五分之一以上。加拿大軍隊於香港保衞戰中奮勇抗敵,他們英勇的事蹟值得特別表揚。是次圖片展亦正好向於戰爭中犧牲的人致敬。

展覽透過一批珍貴的歷史圖片及文字展板,回顧加拿大軍隊參與保衞香港的英勇行為,當中更包括一頭隨軍團來港的加拿大犬─根達參與抗敵的感人故事。根達在鯉魚門(即現時海防博物館一帶)的戰役中奮力保護同袍,最後犧牲性命。//

1941年嘅戰爭其實近乎全香港動員

正面作戰就有英/加/印/防衛軍 /華人軍團,但其他人都喺其他崗位支援作戰

例如「灣仔天使」就送水送食物俾英軍,有教會修士加入揸救護車,有警察加入戰鬥而陣亡,有後備警察幫手維持秩序,華人防空救護員。更加未計之後加入英軍服務團/香港志願連嘅人。

正面作戰就有英/加/印/防衛軍 /華人軍團,但其他人都喺其他崗位支援作戰

例如「灣仔天使」就送水送食物俾英軍,有教會修士加入揸救護車,有警察加入戰鬥而陣亡,有後備警察幫手維持秩序,華人防空救護員。更加未計之後加入英軍服務團/香港志願連嘅人。

加拿大兵戰死好多人,葬係 西灣國殤紀念墳場,有時間去睇吓

//THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE

西灣國殤紀念墳場位於柴灣以南,為安葬二戰時在戰場上犧牲或被俘後死亡人士的主要墳場,共有1578個墳墓,當中包括59個海軍,1406個陸軍,67個空軍,18個商船隊隊員,20個本地抗戰軍人和8個平民,屬英聯邦戰爭公墓委員會(Commonwealth War Graves Commission)所管理。墳場的入口是間白石小屋,屋外刻上墳場名字,還有一把長劍分開「1939」年和「1945」年兩個年份,進去後抬頭細看,牆上刻滿了密密麻麻的名字,遠看像小蛇,是2071名戰時殉難卻無法尋回屍體的士兵名字,當中1319人來自英國軍隊、228人來自加拿大軍隊、287人來自印度軍隊、237人為本地士兵,深刻得如同刻住歷史。另有兩塊石碑,一塊記下144位遺體被火葬的印度軍人與錫克教軍人的姓名,其中9位隸屬香港及新加坡皇家炮兵團,118位隸屬印度軍,17人隸屬香港警隊;另一塊石碑則記下72位二戰時在中國各戰場殉難的英聯邦軍人。

西灣國殤墳場內的墓碑劃一而整齊,令人有肅寧之感。(劉焌陶攝)

加拿大少兵 離鄉來港陣亡

「二戰時,歐美國家多派兵到亞洲幫助抗日,如澳洲士兵派往新加坡,新西蘭軍人則往馬來亞與緬甸,加拿大兵則送往香港。」嶺南大學香港與華南歷史研究部高級項目主任周家建於加拿大成長,熟知當地歷史,他說,這批加拿大兵多自鄉間地方長大,年紀不過十八十九。他們聚集在溫哥華後便坐船到香港,一九四一年十一月抵港,他們自尖沙嘴九龍倉碼頭上岸後,沿彌敦道一直操兵至深水埗,「操兵是一種姿態,一是向日本人表示,他們不會放棄香港;二是向香港人表示,他們一定會堅守香港這個地方」。這班年輕的加拿大兵的日記寫滿了對香港的回憶:「從未見過如香港般繁華的城市」、「香港的夜生活令人大開眼界」、「香港美女如雲」、「地方優美」。美好的日子不過片刻,1997個被派往香港的加拿大兵,三分之一人最後在香港陣亡。

Lawson之墓。(劉焌陶攝)

加國最高將領戰死 日軍立木條紀念

在墓園漫步,青草地上一塊塊白碑無語,只有工人提着水桶,一遍又一遍往墓碑上掃上藥水,以防生苔,難怪一塊塊碑都無比潔白——John Kelburne Lawson的墓就在小道旁邊,碑上有象徽加國的楓葉,碑下小草中一直有小白蝶繞而不散。Lawson是加拿大軍官,是當時駐港加兵的最高將領,到港後,他被遣派到西旅,即現時的黃泥涌峽作指揮官,十二月十九日上午時分,日軍包圍Lawson的總部。他用無線電通知上司,指自己將「Fight it out」,然後雙手各拿一把手槍,衝出總部戰鬥中喪生。「日本人安葬這位加拿大軍官,更在他的總部外立了兩支木條,其中一支是為了紀念他的,但不要覺得日本人對他特別好,此舉只是日本人對死亡另有想法,對戰爭上死去的人有一份尊重罷了。」

「你最忠誠的兒子, John」獄中撰給母親的家書

另一位加拿大步兵John Payne的墓就在Lawson的不遠處——他並非在戰場上戰死的士兵,亦不是在香港保衛戰中的十八日中死去,而是在被日軍囚禁期間嘗試在深水埗集中營逃走而被殺。「被敵軍囚禁拼死逃跑是軍人的天職」,周家建扶着墓碑,輕輕說道,「談到香港保衛戰,我們都會提到John Payne在囚禁期間寫的信。」John Payne在獄中寫了好幾封信給他的sweetheart和母親,但他並沒有把這些信寄出去,「當時寄信手續比較轉折,要經過審查,是故他只把寫給媽媽的信交給同囚的同胞Manchester,Manchester把他的信緊緊收在自己的軍服中,直到戰後才把信給John Payne的媽媽,John Payne當時跟Manchester說的那句「請將信交給我母親,我們將會在溫尼伯再見(Get that letter to my mother. I will meet you all in Winnipeg.)」卻始終無法成真。//

https://www.pentoy.hk/%E4%B8%83%E5%8D%81%E5%B9%B4%E7%94%9F%E6%AD%BB%E5%85%A9%E8%8C%AB%E3%80%80%E8%A5%BF%E7%81%A3%E5%9C%8B%E6%AE%A4%E7%B4%80%E5%BF%B5%E5%A2%B3%E5%A0%B4%E3%80%80%E5%BE%9E%E5%A2%93%E7%A2%91%E8%AA%AA%E6%88%B0/

西灣國殤紀念墳場位於柴灣以南,為安葬二戰時在戰場上犧牲或被俘後死亡人士的主要墳場,共有1578個墳墓,當中包括59個海軍,1406個陸軍,67個空軍,18個商船隊隊員,20個本地抗戰軍人和8個平民,屬英聯邦戰爭公墓委員會(Commonwealth War Graves Commission)所管理。墳場的入口是間白石小屋,屋外刻上墳場名字,還有一把長劍分開「1939」年和「1945」年兩個年份,進去後抬頭細看,牆上刻滿了密密麻麻的名字,遠看像小蛇,是2071名戰時殉難卻無法尋回屍體的士兵名字,當中1319人來自英國軍隊、228人來自加拿大軍隊、287人來自印度軍隊、237人為本地士兵,深刻得如同刻住歷史。另有兩塊石碑,一塊記下144位遺體被火葬的印度軍人與錫克教軍人的姓名,其中9位隸屬香港及新加坡皇家炮兵團,118位隸屬印度軍,17人隸屬香港警隊;另一塊石碑則記下72位二戰時在中國各戰場殉難的英聯邦軍人。

西灣國殤墳場內的墓碑劃一而整齊,令人有肅寧之感。(劉焌陶攝)

加拿大少兵 離鄉來港陣亡

「二戰時,歐美國家多派兵到亞洲幫助抗日,如澳洲士兵派往新加坡,新西蘭軍人則往馬來亞與緬甸,加拿大兵則送往香港。」嶺南大學香港與華南歷史研究部高級項目主任周家建於加拿大成長,熟知當地歷史,他說,這批加拿大兵多自鄉間地方長大,年紀不過十八十九。他們聚集在溫哥華後便坐船到香港,一九四一年十一月抵港,他們自尖沙嘴九龍倉碼頭上岸後,沿彌敦道一直操兵至深水埗,「操兵是一種姿態,一是向日本人表示,他們不會放棄香港;二是向香港人表示,他們一定會堅守香港這個地方」。這班年輕的加拿大兵的日記寫滿了對香港的回憶:「從未見過如香港般繁華的城市」、「香港的夜生活令人大開眼界」、「香港美女如雲」、「地方優美」。美好的日子不過片刻,1997個被派往香港的加拿大兵,三分之一人最後在香港陣亡。

Lawson之墓。(劉焌陶攝)

加國最高將領戰死 日軍立木條紀念

在墓園漫步,青草地上一塊塊白碑無語,只有工人提着水桶,一遍又一遍往墓碑上掃上藥水,以防生苔,難怪一塊塊碑都無比潔白——John Kelburne Lawson的墓就在小道旁邊,碑上有象徽加國的楓葉,碑下小草中一直有小白蝶繞而不散。Lawson是加拿大軍官,是當時駐港加兵的最高將領,到港後,他被遣派到西旅,即現時的黃泥涌峽作指揮官,十二月十九日上午時分,日軍包圍Lawson的總部。他用無線電通知上司,指自己將「Fight it out」,然後雙手各拿一把手槍,衝出總部戰鬥中喪生。「日本人安葬這位加拿大軍官,更在他的總部外立了兩支木條,其中一支是為了紀念他的,但不要覺得日本人對他特別好,此舉只是日本人對死亡另有想法,對戰爭上死去的人有一份尊重罷了。」

「你最忠誠的兒子, John」獄中撰給母親的家書

另一位加拿大步兵John Payne的墓就在Lawson的不遠處——他並非在戰場上戰死的士兵,亦不是在香港保衛戰中的十八日中死去,而是在被日軍囚禁期間嘗試在深水埗集中營逃走而被殺。「被敵軍囚禁拼死逃跑是軍人的天職」,周家建扶着墓碑,輕輕說道,「談到香港保衛戰,我們都會提到John Payne在囚禁期間寫的信。」John Payne在獄中寫了好幾封信給他的sweetheart和母親,但他並沒有把這些信寄出去,「當時寄信手續比較轉折,要經過審查,是故他只把寫給媽媽的信交給同囚的同胞Manchester,Manchester把他的信緊緊收在自己的軍服中,直到戰後才把信給John Payne的媽媽,John Payne當時跟Manchester說的那句「請將信交給我母親,我們將會在溫尼伯再見(Get that letter to my mother. I will meet you all in Winnipeg.)」卻始終無法成真。//

https://www.pentoy.hk/%E4%B8%83%E5%8D%81%E5%B9%B4%E7%94%9F%E6%AD%BB%E5%85%A9%E8%8C%AB%E3%80%80%E8%A5%BF%E7%81%A3%E5%9C%8B%E6%AE%A4%E7%B4%80%E5%BF%B5%E5%A2%B3%E5%A0%B4%E3%80%80%E5%BE%9E%E5%A2%93%E7%A2%91%E8%AA%AA%E6%88%B0/

https://hk.coastaldefence.museum/zh_TW/web/mcd/exhibition/pastexhibitions/pastexhibitions20.html

一九四一年十一月十六日,兩營加拿大部隊 ─ 溫尼伯榴彈兵營與加拿大皇家來福槍營,乘坐巨型運輸艦抵港增援。這支軍隊連同文職及後勤支援為數共約二千五百人,在羅遜准將的率領下,立即加入香港守軍的行列。抵港部隊裡絕大部分是非常年青的新兵,缺乏嚴格訓練,更沒有作戰經驗,對香港的地形也不太熟悉,再加上他們的裝備未及抵港,大大削弱其戰鬥力。當日軍於十二月八日對香港展開進攻後,到聖誕日港督楊慕琦宣布投降,不少加拿大守軍陣亡,當中包括在黃泥涌峽壯烈戰死的羅遜准將。淪陷後,加拿大部隊被囚禁在集中營內,當中也有不少因疾病、營養不良等原因而不幸去世。總計自香港保衛戰至三年零八個月的歲月共有逾五百名加拿大部隊成員在港去世,佔到港參與保衛香港的人數逾五分之一;戰後多葬於赤柱軍人墳場和西灣國殤墳場。每年加拿大駐港總領事館都會舉行儀式以作悼念,當年曾參與的老兵都會重臨香港出席。二零一一年是香港保衛戰七十周年,是次圖片展覽正是向保衛香港的加拿大部隊致敬。

一九四一年十一月十六日,兩營加拿大部隊 ─ 溫尼伯榴彈兵營與加拿大皇家來福槍營,乘坐巨型運輸艦抵港增援。這支軍隊連同文職及後勤支援為數共約二千五百人,在羅遜准將的率領下,立即加入香港守軍的行列。抵港部隊裡絕大部分是非常年青的新兵,缺乏嚴格訓練,更沒有作戰經驗,對香港的地形也不太熟悉,再加上他們的裝備未及抵港,大大削弱其戰鬥力。當日軍於十二月八日對香港展開進攻後,到聖誕日港督楊慕琦宣布投降,不少加拿大守軍陣亡,當中包括在黃泥涌峽壯烈戰死的羅遜准將。淪陷後,加拿大部隊被囚禁在集中營內,當中也有不少因疾病、營養不良等原因而不幸去世。總計自香港保衛戰至三年零八個月的歲月共有逾五百名加拿大部隊成員在港去世,佔到港參與保衛香港的人數逾五分之一;戰後多葬於赤柱軍人墳場和西灣國殤墳場。每年加拿大駐港總領事館都會舉行儀式以作悼念,當年曾參與的老兵都會重臨香港出席。二零一一年是香港保衛戰七十周年,是次圖片展覽正是向保衛香港的加拿大部隊致敬。

https://www.cup.com.hk/2018/11/30/grey-canadian-commemorative-ceremony/

1941 年 10 月 23 日,加拿大皇家來福槍營官兵由魁北克前往溫哥華港口,準備出發赴港參戰。 圖片來源:香港海防博物館/政府新聞處

上文提到 11 月 11 日是和平紀念日(Remembrance Sunday),但其實 12 月還有另一個與香港保衛戰有關的日子 —— 加拿大和平紀念儀式 (Canadian Commemorative Ceremony)。雖然同屬英聯邦,但加拿大、澳紐等國因為歷史因素各自亦有紀念儀式及戰爭紀念日。

1941 年 11 月 16 日,在香港保衛戰爆發前夕,兩營加拿大援軍經海路抵港,應對日軍威脅。兩營加軍屬溫尼伯榴彈兵營(Winnipeg Grenadiers)及加拿大皇家來福槍營(Royal Rifles of Canada),人數約 2,000 人(註)。由於當年盟軍估計日軍在短期內向不會向英國宣戰,所以安排加拿大士兵到港原意是來香港接受訓練,為戰事作準備。

加拿大軍隊抵港,經彌敦道前往深水埗軍營。 圖片來源:香港海防博物館/政府新聞處

但一切出乎意料,日軍於 12 月 8 日展開「南方作戰」猛攻香港、馬來半島等地,加拿大援軍則協助英軍成為防衛香港及反攻主力。加軍於訓練不足及欠缺裝備的情況下依然拼死力戰,英勇事跡不能盡錄。由於有人數及裝備上優勢,日軍原先打算一星期內可以完全控制香港,但遭守軍負隅頑抗,戰事非常激烈。

12 月 19 日凌晨時分,一隊由軍士長(Company Sergeant Major)約翰・奧斯本(John Robert Osborn)帶領的溫尼伯榴彈兵,撒退至近渣甸山碉堡時遭日軍槍炮及手榴彈強攻。奧斯本原先將手榴彈掟回日軍,但無法完全化解攻勢。在生死關頭,奧斯本以肉身覆蓋手榴彈,犧牲自己保護同袍生命。奧斯本死後獲追頒英聯邦最高榮譽的維多利亞十字勛章。

香港保衛戰 18 日戰事中,加拿大軍有近 300 人戰死,包括領軍突圍的加軍指揮官羅遜准將(Brigadier John K. Lawson),另外傷者過半。超過 200 人在被俘期間因為營養不良、欠缺藥物治療或被日軍虐待至死,後來葬於香港島西灣國殤紀念墳場,青山有幸埋忠骨。

在本年的 12 月 2 日早上,加拿大領事館在西灣國殤紀念墳場會有悼念活動。各位亦可以向香港公園內英軍銅像獻花,以紀念香港保衛戰中殉職軍民。

We will remember them.

註:網上資料普遍指援軍人數約 2,500 人,但該資料無列明出處;英媒 BBC 報道指援軍人數有 1,975 人。

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=mPLyGYhbedE

加拿大史館(Historica Canada)曾拍攝紀綠片講述軍士長奧斯本的英勇事跡。

1941 年 10 月 23 日,加拿大皇家來福槍營官兵由魁北克前往溫哥華港口,準備出發赴港參戰。 圖片來源:香港海防博物館/政府新聞處

上文提到 11 月 11 日是和平紀念日(Remembrance Sunday),但其實 12 月還有另一個與香港保衛戰有關的日子 —— 加拿大和平紀念儀式 (Canadian Commemorative Ceremony)。雖然同屬英聯邦,但加拿大、澳紐等國因為歷史因素各自亦有紀念儀式及戰爭紀念日。

1941 年 11 月 16 日,在香港保衛戰爆發前夕,兩營加拿大援軍經海路抵港,應對日軍威脅。兩營加軍屬溫尼伯榴彈兵營(Winnipeg Grenadiers)及加拿大皇家來福槍營(Royal Rifles of Canada),人數約 2,000 人(註)。由於當年盟軍估計日軍在短期內向不會向英國宣戰,所以安排加拿大士兵到港原意是來香港接受訓練,為戰事作準備。

加拿大軍隊抵港,經彌敦道前往深水埗軍營。 圖片來源:香港海防博物館/政府新聞處

但一切出乎意料,日軍於 12 月 8 日展開「南方作戰」猛攻香港、馬來半島等地,加拿大援軍則協助英軍成為防衛香港及反攻主力。加軍於訓練不足及欠缺裝備的情況下依然拼死力戰,英勇事跡不能盡錄。由於有人數及裝備上優勢,日軍原先打算一星期內可以完全控制香港,但遭守軍負隅頑抗,戰事非常激烈。

12 月 19 日凌晨時分,一隊由軍士長(Company Sergeant Major)約翰・奧斯本(John Robert Osborn)帶領的溫尼伯榴彈兵,撒退至近渣甸山碉堡時遭日軍槍炮及手榴彈強攻。奧斯本原先將手榴彈掟回日軍,但無法完全化解攻勢。在生死關頭,奧斯本以肉身覆蓋手榴彈,犧牲自己保護同袍生命。奧斯本死後獲追頒英聯邦最高榮譽的維多利亞十字勛章。

香港保衛戰 18 日戰事中,加拿大軍有近 300 人戰死,包括領軍突圍的加軍指揮官羅遜准將(Brigadier John K. Lawson),另外傷者過半。超過 200 人在被俘期間因為營養不良、欠缺藥物治療或被日軍虐待至死,後來葬於香港島西灣國殤紀念墳場,青山有幸埋忠骨。

在本年的 12 月 2 日早上,加拿大領事館在西灣國殤紀念墳場會有悼念活動。各位亦可以向香港公園內英軍銅像獻花,以紀念香港保衛戰中殉職軍民。

We will remember them.

註:網上資料普遍指援軍人數約 2,500 人,但該資料無列明出處;英媒 BBC 報道指援軍人數有 1,975 人。

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=mPLyGYhbedE

加拿大史館(Historica Canada)曾拍攝紀綠片講述軍士長奧斯本的英勇事跡。

Winnipeg Grenadiers

Royal Rifles of Canada

Royal Rifles of Canada

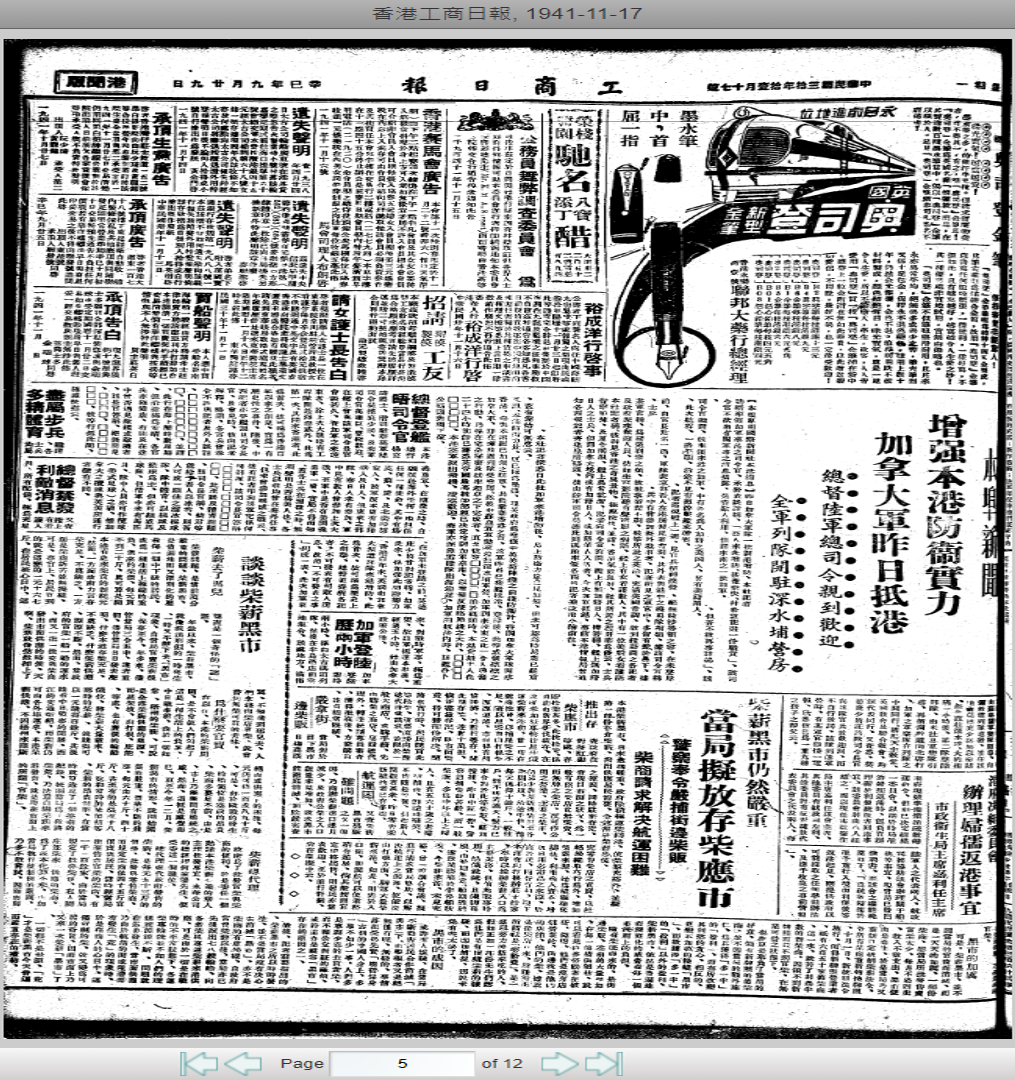

香港工商日報, 1941-11-17

自推

//

Canadian Prisoners of War

Canadian Prisoners of War captured during the battle of Hong Kong, 25 December 1941. Individuals shown here were part of a group sent from Hong Kong to Japan on 19 January 1943.

(courtesy Larry Stebbe/The Memory Project)

Why Canadian Troops Went to Hong Kong

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but the Canadian Army saw little action in the early years of the conflict. For one thing, Canada’s military was small and unprepared for war. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was also cautious about committing the country to battle. After the heavy bloodletting and the domestic divisions of the First World War, King was wary of sending large numbers of soldiers to fight overseas — something that might require conscription and re-ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Instead, King sought other ways for Canada to help the war effort, such as making armaments, growing food and training air crews under the new British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (See Mackenzie King and the War Effort.)

The Royal Canadian Navy had been involved in the Battle of the Atlantic since 1939, and Canadian airmen had made a small contribution to the Battle of Britain, but the Army was not actively engaged in the war — despite growing pressure among English Canadians for a greater role. So in 1941, when Britain made a request for Canadian troops to help bolster its remote Asian colony of Hong Kong, the King government agreed to send two battalions overseas, for what it assumed would merely be garrison duty.

Hong Kong in November 1941

Japan had been waging war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. By 1940, the British were fighting for survival against Germany. They realized that defending Hong Kong would be virtually impossible if the colony, and other Asian possessions, were attacked by Japan. Even so, Britain decided that a show of force might deter any possible Japanese aggression, and it sought troops to reinforce the British and Indian units already garrisoned in Hong Kong.

The King government agreed to dispatch two battalions. Harry Crerar, chief of the general staff, assigned the task to the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec City). Both units had some experience serving on garrison duty; however, neither was at full strength in 1941, or adequately trained for the modern warfare of the time. Neither regiment had even participated in battalion-level training exercises. No matter — a Japanese attack against British territories in the Pacific seemed unlikely. Even if one came, the prevailing racial attitudes of the time convinced many Canadian and British military leaders that superior White troops would teach the Japanese a lesson.

The two undermanned Canadian battalions were quickly filled out with additions of new, inexperienced troops and shipped across the Pacific, under the command of Brigadier J.K. Lawson. The force included 1,973 officers and men plus two nursing sisters. It arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November, joining a military garrison that now totalled about 14,000.//

//On Christmas Day, with ammunition in short supply and the defending soldiers in desperate shape, “D” company of the Royal Rifles was ordered to make what appeared to be a suicidal attack to retake lost ground at the south end of the island. According to an account from Sergeant George MacDonnell, the men received the orders in stunned silence. “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Attacking with bayonets, the Royal Rifles succeeded in taking the position — at a cost of 26 men killed and 75 wounded. Hours later, the exhausted survivors learned that the colony had surrendered. The Battle of Hong Kong was over.//

Canadian Prisoners of War

Canadian Prisoners of War captured during the battle of Hong Kong, 25 December 1941. Individuals shown here were part of a group sent from Hong Kong to Japan on 19 January 1943.

(courtesy Larry Stebbe/The Memory Project)

Why Canadian Troops Went to Hong Kong

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but the Canadian Army saw little action in the early years of the conflict. For one thing, Canada’s military was small and unprepared for war. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was also cautious about committing the country to battle. After the heavy bloodletting and the domestic divisions of the First World War, King was wary of sending large numbers of soldiers to fight overseas — something that might require conscription and re-ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Instead, King sought other ways for Canada to help the war effort, such as making armaments, growing food and training air crews under the new British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (See Mackenzie King and the War Effort.)

The Royal Canadian Navy had been involved in the Battle of the Atlantic since 1939, and Canadian airmen had made a small contribution to the Battle of Britain, but the Army was not actively engaged in the war — despite growing pressure among English Canadians for a greater role. So in 1941, when Britain made a request for Canadian troops to help bolster its remote Asian colony of Hong Kong, the King government agreed to send two battalions overseas, for what it assumed would merely be garrison duty.

Hong Kong in November 1941

Japan had been waging war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. By 1940, the British were fighting for survival against Germany. They realized that defending Hong Kong would be virtually impossible if the colony, and other Asian possessions, were attacked by Japan. Even so, Britain decided that a show of force might deter any possible Japanese aggression, and it sought troops to reinforce the British and Indian units already garrisoned in Hong Kong.

The King government agreed to dispatch two battalions. Harry Crerar, chief of the general staff, assigned the task to the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec City). Both units had some experience serving on garrison duty; however, neither was at full strength in 1941, or adequately trained for the modern warfare of the time. Neither regiment had even participated in battalion-level training exercises. No matter — a Japanese attack against British territories in the Pacific seemed unlikely. Even if one came, the prevailing racial attitudes of the time convinced many Canadian and British military leaders that superior White troops would teach the Japanese a lesson.

The two undermanned Canadian battalions were quickly filled out with additions of new, inexperienced troops and shipped across the Pacific, under the command of Brigadier J.K. Lawson. The force included 1,973 officers and men plus two nursing sisters. It arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November, joining a military garrison that now totalled about 14,000.//

//On Christmas Day, with ammunition in short supply and the defending soldiers in desperate shape, “D” company of the Royal Rifles was ordered to make what appeared to be a suicidal attack to retake lost ground at the south end of the island. According to an account from Sergeant George MacDonnell, the men received the orders in stunned silence. “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Attacking with bayonets, the Royal Rifles succeeded in taking the position — at a cost of 26 men killed and 75 wounded. Hours later, the exhausted survivors learned that the colony had surrendered. The Battle of Hong Kong was over.//

//

Canadian Prisoners of War

Canadian Prisoners of War captured during the battle of Hong Kong, 25 December 1941. Individuals shown here were part of a group sent from Hong Kong to Japan on 19 January 1943.

(courtesy Larry Stebbe/The Memory Project)

Why Canadian Troops Went to Hong Kong

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but the Canadian Army saw little action in the early years of the conflict. For one thing, Canada’s military was small and unprepared for war. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was also cautious about committing the country to battle. After the heavy bloodletting and the domestic divisions of the First World War, King was wary of sending large numbers of soldiers to fight overseas — something that might require conscription and re-ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Instead, King sought other ways for Canada to help the war effort, such as making armaments, growing food and training air crews under the new British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (See Mackenzie King and the War Effort.)

The Royal Canadian Navy had been involved in the Battle of the Atlantic since 1939, and Canadian airmen had made a small contribution to the Battle of Britain, but the Army was not actively engaged in the war — despite growing pressure among English Canadians for a greater role. So in 1941, when Britain made a request for Canadian troops to help bolster its remote Asian colony of Hong Kong, the King government agreed to send two battalions overseas, for what it assumed would merely be garrison duty.

Hong Kong in November 1941

Japan had been waging war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. By 1940, the British were fighting for survival against Germany. They realized that defending Hong Kong would be virtually impossible if the colony, and other Asian possessions, were attacked by Japan. Even so, Britain decided that a show of force might deter any possible Japanese aggression, and it sought troops to reinforce the British and Indian units already garrisoned in Hong Kong.

The King government agreed to dispatch two battalions. Harry Crerar, chief of the general staff, assigned the task to the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec City). Both units had some experience serving on garrison duty; however, neither was at full strength in 1941, or adequately trained for the modern warfare of the time. Neither regiment had even participated in battalion-level training exercises. No matter — a Japanese attack against British territories in the Pacific seemed unlikely. Even if one came, the prevailing racial attitudes of the time convinced many Canadian and British military leaders that superior White troops would teach the Japanese a lesson.

The two undermanned Canadian battalions were quickly filled out with additions of new, inexperienced troops and shipped across the Pacific, under the command of Brigadier J.K. Lawson. The force included 1,973 officers and men plus two nursing sisters. It arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November, joining a military garrison that now totalled about 14,000.//

//On Christmas Day, with ammunition in short supply and the defending soldiers in desperate shape, “D” company of the Royal Rifles was ordered to make what appeared to be a suicidal attack to retake lost ground at the south end of the island. According to an account from Sergeant George MacDonnell, the men received the orders in stunned silence. “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Attacking with bayonets, the Royal Rifles succeeded in taking the position — at a cost of 26 men killed and 75 wounded. Hours later, the exhausted survivors learned that the colony had surrendered. The Battle of Hong Kong was over.//

Canadian Prisoners of War

Canadian Prisoners of War captured during the battle of Hong Kong, 25 December 1941. Individuals shown here were part of a group sent from Hong Kong to Japan on 19 January 1943.

(courtesy Larry Stebbe/The Memory Project)

Why Canadian Troops Went to Hong Kong

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but the Canadian Army saw little action in the early years of the conflict. For one thing, Canada’s military was small and unprepared for war. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was also cautious about committing the country to battle. After the heavy bloodletting and the domestic divisions of the First World War, King was wary of sending large numbers of soldiers to fight overseas — something that might require conscription and re-ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Instead, King sought other ways for Canada to help the war effort, such as making armaments, growing food and training air crews under the new British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (See Mackenzie King and the War Effort.)

The Royal Canadian Navy had been involved in the Battle of the Atlantic since 1939, and Canadian airmen had made a small contribution to the Battle of Britain, but the Army was not actively engaged in the war — despite growing pressure among English Canadians for a greater role. So in 1941, when Britain made a request for Canadian troops to help bolster its remote Asian colony of Hong Kong, the King government agreed to send two battalions overseas, for what it assumed would merely be garrison duty.

Hong Kong in November 1941

Japan had been waging war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. By 1940, the British were fighting for survival against Germany. They realized that defending Hong Kong would be virtually impossible if the colony, and other Asian possessions, were attacked by Japan. Even so, Britain decided that a show of force might deter any possible Japanese aggression, and it sought troops to reinforce the British and Indian units already garrisoned in Hong Kong.

The King government agreed to dispatch two battalions. Harry Crerar, chief of the general staff, assigned the task to the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec City). Both units had some experience serving on garrison duty; however, neither was at full strength in 1941, or adequately trained for the modern warfare of the time. Neither regiment had even participated in battalion-level training exercises. No matter — a Japanese attack against British territories in the Pacific seemed unlikely. Even if one came, the prevailing racial attitudes of the time convinced many Canadian and British military leaders that superior White troops would teach the Japanese a lesson.

The two undermanned Canadian battalions were quickly filled out with additions of new, inexperienced troops and shipped across the Pacific, under the command of Brigadier J.K. Lawson. The force included 1,973 officers and men plus two nursing sisters. It arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November, joining a military garrison that now totalled about 14,000.//

//On Christmas Day, with ammunition in short supply and the defending soldiers in desperate shape, “D” company of the Royal Rifles was ordered to make what appeared to be a suicidal attack to retake lost ground at the south end of the island. According to an account from Sergeant George MacDonnell, the men received the orders in stunned silence. “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Attacking with bayonets, the Royal Rifles succeeded in taking the position — at a cost of 26 men killed and 75 wounded. Hours later, the exhausted survivors learned that the colony had surrendered. The Battle of Hong Kong was over.//

//Memory

Of the 1,975 Canadians sent to Hong Kong, 290 were killed and 493 wounded during the battle and its immediate aftermath — proof, said veterans decades later, that they had resisted fiercely and courageously before surrendering to the enemy. Another 264 Canadians died as prisoners of war, while 1,418 survivors returned to Canada — many of them deeply bitter at the cruelty of their Japanese captors.

At home, political pressure forced the government in Ottawa to appoint a royal commission to investigate the circumstances of Canada’s involvement in Hong Kong. The sole commissioner, Chief Justice Lyman Duff, misinterpreted or ignored evidence and exonerated the Cabinet, the Department of National Defence and senior members of the military’s general staff. In 1948, a confidential analysis by General Charles Foulkes, chief of the general staff, found many errors in Duff’s assessment, but concluded that proper training, staffing and equipment would have made little difference, given the overwhelming odds facing the defenders.

The 554 Canadians who died in Hong Kong and in prisoner camps afterwards are remembered today by a memorial to all of Hong Kong’s defenders at the Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery there. This and the Stanley Military Cemetery in Hong Kong also hold the individual graves of 303 Canadian soldiers, 108 of whom are unidentified. Another 137 Canadians, most of whom died as prisoners of war, are buried at the British Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama, Japan.//

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-hong-kong

Of the 1,975 Canadians sent to Hong Kong, 290 were killed and 493 wounded during the battle and its immediate aftermath — proof, said veterans decades later, that they had resisted fiercely and courageously before surrendering to the enemy. Another 264 Canadians died as prisoners of war, while 1,418 survivors returned to Canada — many of them deeply bitter at the cruelty of their Japanese captors.

At home, political pressure forced the government in Ottawa to appoint a royal commission to investigate the circumstances of Canada’s involvement in Hong Kong. The sole commissioner, Chief Justice Lyman Duff, misinterpreted or ignored evidence and exonerated the Cabinet, the Department of National Defence and senior members of the military’s general staff. In 1948, a confidential analysis by General Charles Foulkes, chief of the general staff, found many errors in Duff’s assessment, but concluded that proper training, staffing and equipment would have made little difference, given the overwhelming odds facing the defenders.

The 554 Canadians who died in Hong Kong and in prisoner camps afterwards are remembered today by a memorial to all of Hong Kong’s defenders at the Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery there. This and the Stanley Military Cemetery in Hong Kong also hold the individual graves of 303 Canadian soldiers, 108 of whom are unidentified. Another 137 Canadians, most of whom died as prisoners of war, are buried at the British Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama, Japan.//

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-hong-kong

大部份人逃出後

最後都戰死係淺水灣

最後都戰死係淺水灣

Pushhh

加拿大駐兵香港嘅用意係威攝日本,但日本已經選擇郁手,而且考慮到處於喺兵力劣勢,加拿大軍如果喺死傷慘重前投降亦無可厚非。但喺英國政府眼中,香港之戰係鼓舞中國政府繼續打嘅意思,所以兩邊各有道理。未到聖誕節之前,總司令莫德庇其實有諗過及早投降,但倫敦嘅命令係繼續打,所以先再打到聖誕節。其間佢同加拿大軍嘅人有爭執過依件事。

戰後佢去咗加拿大,亦絕口不提香港嘅事。

有人認為英國水咗加軍去送死,但亦有相反意件,依樣我個人認為就見仁見智,但無可否認嘅係,加軍同其他部隊都打得好英勇。

pinned, thanks